LAS VENICE (About, English version)

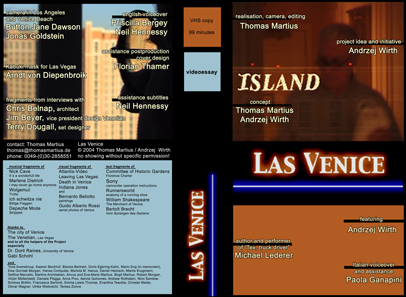

Andrzej Wirth, founder of applied theater studies in Germany and cultural critic and Thomas Martius, videomaker and performance artist, investigate together the "original" laguna city of Venice and its replica at the "Venetian" casinohotel in Las Vegas.

Tourists armed with camcorders and flash cameras let a familiar postcard scenery flow into the lenses of their equipment. There is no need to focus in arcadia, everthing is certified as a beauty. On Rialto and Ponte dell`Academia cameras are handed to strangers, "I will immortalize myself" one hears in all languages. What a kind of communicative transaction is that? The disneyfied City of Sin on the Nevada Desert and the sinking Laguna City are shown as "walk in installations", with the scenery stronger as the moving figures. The scenery casts the walkers in a role and exercises on them a clandestine act of directing. They became virtual actors, we call them "vactors". Vegas was build for the tourists as a selfexplanatory installation. Venice is a remnant of history familiar, but for visitors despite all available guides an enigma.

The piece is a mixed genre, between documentary and essayistic videoperformance with one actor/writer casted in a selfdeviced role of a casino visitor (Michael Lederer), with a notorious mentor and commentator, who plays himself (Andrzej Wirth), and with a director hidden behind the moving pictures (Thomas Martius). Moving on many levels the piece returnes to its center, reflexion on ephemeric nature of life and theater.

LAS VENICE (About, auf Deutsch)

Andrzej Wirth, Begründer des Institutes der Angewandten Theaterwissenschaft in Gießen, und Thomas Martius gemeinsam am „Originalort“ Venedig und in seiner Kopie im Casinohotel „Venetian“ in Las Vegas ...

Sich selbstverewigend erschießen die Touristen mit ihren Blitzkameras die berühmten Bauten, die ihnen von Postkarten her bereits bekannt sind. Die disneyfizierte Sin City in der Wüste Nevadas und die sinkende Lagunenstadt werden als „walk-in-installations“ vorgeführt, in denen die Akteure zu „Vactors“ werden, zu „virtual actors“. Vegas für Touristen gebaut, Venice ein left over der Geschichte, nicht mehr entzifferbar.

Eine essayistische Videoperformance, auf vielen Ebenen unterwegs und doch ein Zentrum umkreisend: die eigene Kurzlebigkeit und die des Theaters.

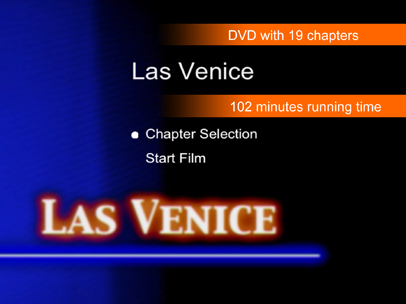

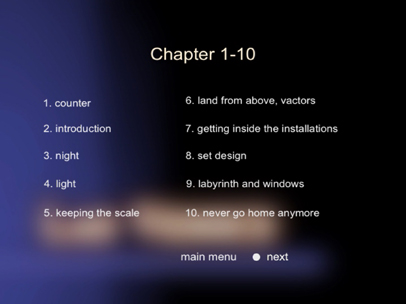

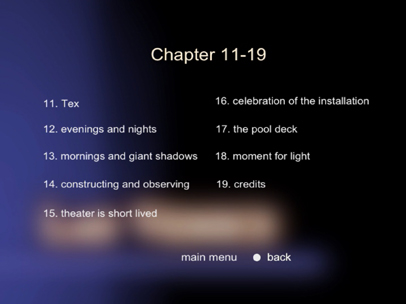

The DVD-Chapters

Former Project Descriptions

in English, German and Italian

(before filming the Las Vegas-part)

Project Description, 2002

(English)

Andrzej Wirth and Thomas Martius were together on tour in Italy, at the „original location“ of Venice. Now they meet again: at the „Venetian“, the reproduction of Venice in Las Vegas. Both cities can be considered labyrinthic theatres. Any visitor inevitably becomes a stage figur. What are the differences between the stagings in Venice and at the Venetian? What will Andrzej Wirth say about this? And how will Thomas Martius set the happenings into moving pictures? An entertaining video-essay possibly could come out of this, fiction and documentary at the same time.

Vactor in Venice (Video, 45 minutes, 2001)

Venice is shown as a „walk-in-installation“. Within the scenery of the city any visitor inevitably becomes a „vactor“, a „virtual actor“, always „on display“. Like a stage figure one steps inside various frames and steps out again, always on stage and watching the stage. In front of the famous buildings, already known from the postcards, the tourists try to perpetuate themselves on photos and videos. They exchange their cameras with each other. Among these happenings Andrzej Wirth introduces his „Vactor“-concept and becomes one himself. The applied theatre-theorist as an observer. Talking about what he sees in Venice and how that relates to former observations of his life. From Warsaw via Brecht to Kennedy.

Accompanying a lecture the video so far was presented to specialised audiences at various places: Venice, Berlin, Frankfurt, Los Angeles, New York, Breslau and others. Some footage of this video might be of use for the new work. It may contrast with captured scenes from Las Vegas and might make the authenticity of the pictures even more doubtful: „What is an original anyway?“.

A copy of the rough draft „Vactor in Venice“ is available anytime.

What is an original anyway? (working title, 2002)

As in Venice so in Las Vegas the visitor is part of a secenery that, once he is there, he can`t remove from. In the 60s the visitor reached the (after Mekka) most visited pilgrim`s place with a car. Nowadays he lands with an airplane, every minute. Correspondingly the Strip has changed. Two-dimensional signs, neon advertising and colourful facades installed for 35mph driving by cars have been substituted by pixels and artitficial landscapes in front of the buildings: a development from the sign to the secene.

Within the 90s Las Vegas changed successfully into an entertainment-paradise for the whole family. Martin Scorses called this the „Disneyfication of Sin City“. Storyboards that usually are used in film productions help to plan the adventure-parks first dramaturgically and then architecturally, in the last analysis always with the aim to increase the consumption of the visitors. Often european tourist-destinations are the references for the new developed theme-parks. Places are quoted whose images are already known from postcards and which can be considered part of a collective memory. Through the sale of their „essence“ these original locations produce a sort of imprint for Las Vegas.

The casino-hotel „Venetian“ is the most current example. The Rialto-bridge and its surroundings have been created once more, life size, under the advice of art historians and with the use of real italian marble. The perfect copy, though, doesn`t claim to be authentic, it means to be a „real fake“. Las Vegas and its visitors are quite conscious about the illusion of this theatre.

But still, when the Venetian opened in 1999 the then mayor of Venice complained that his real city of beauty was being cheated out of its pictures and history. Now Venice tries to reserve a copyright to protect its „essence“ and even develops a „trademark“ in order to provide some security for it.

Venice has already been standardized and multiplied by Hollywood. Las Vegas now goes one step further and makes it possible to experience an authentic reproduction by wandering around inside of it. Whoever gets into „New York, New York“ has a problem getting himself out again: in Las Vegas the labyrinth-effect is used commercially, in Venice it has got its perfect prototype.

What are the differences between the original and the duplicate? In opposite to the tourist in Venice the guest of the Venetian might be less aware of the historical substance, rather experiencing his trip as a member of a touristic mass, making use of the service-rendering offers. He fulfills the adventure-roles that Las Vegas lets him play, but he always keeps on being the paying tourist and is treated as such. On the other side, as it is shown in „Vactor in Venice“, his counterpart the Venice-tourist is also put on stage as a standardized actor in a not more romantic but rather commercial play. At both places the tourists become part of the scenery as soon as they appear inside the scenery.

„What is an original anyway?“ It`s not such a new question, neither in the history of Venice, which itself developed as a composition of copies and different styles, nor in Las Vegas. Already by 1946 the mafia-gangster Bugsy Siegel built a copy of a Hollywood-nightclub inside the Flamingo. Will Andrzej Wirth enjoy life to the full as a gangster in Las Vegas? Or will he be talking about earlier sins? Will he perhaps lose all his money in gambling and become homeless? The task is to interlace the location and the observations with the persona of Andrzej Wirth in a sensible way.

As visitors and observers we are looking for the similarities and differences between the stagings of Venice and Las Vegas. Possibly we will ask some questions to the managers of the Venetian.

The Venetian is built as a world on its own, holding an inside and outside inside its inside itself. Still we will have to risk a step out of this world and will have to wander through uncertain terrains. For example on the way to “New York, New York” where the trash is been taking care of with handcarts, visible for all visitors. The usually hidden service is shown as part of the produced scenery. Just like in Venice, especially the Venice at night. Which of course appears much darker in contrast to the electrified desert-city. And obviously more wet, too.

Projektbeschreibung von 2002

(Deutsch)

Andrzej Wirth und Thomas Martius waren zusammen am „Originalort“ Venedig unterwegs. Jetzt treffen sie sich im „Venetian“, der Reproduktion Venedigs in Las Vegas. Beide Städte sind labyrinthische Theater, in denen jeder Besucher zwangsläufig zur Bühnenfigur wird. Worin unterscheiden sich die Inszenierungen? Was hat Andrzej Wirth dazu zu sagen? Und wie setzt Thomas Martius die Ereignisse ins Bild? Entstehen könnte ein unterhaltsames Video-Essay, das Fiktion und Dokumentation zugleich ist.

Vactor in Venice (Video, 45 Minuten, 2001)

Venedig wird als „walk-in-installation“ gezeigt. In der Kulisse der Stadt wird der Besucher zwangsläufig zum „Vactor“, zum „virtual actor“. Ein jeder ist „always on display“. Wie eine Bühnenfigur tritt er in die unterschiedlichsten Rahmungen hinein bzw. wieder aus ihnen heraus. Die Touristen verewigen sich vor berühmten Bauten, die ihnen von den Postkarten her bereits bekannt sind. Sie tauschen gegenseitig ihre Kameras aus. Mitten darin Andrzej Wirth, der sein Konzept des „Vactors“ vorstellt und dabei selbst zum „Vactor“ wird. Der anwendende Theaterwissenschaftler beobachtet und gibt Beobachtungen aus seinem Leben wieder. Von Warschau über Brecht bis zu Kennedy.

Das Video wurde als Begleitung für einen Vortrag einem spezialisierten Publikum vorgeführt: u.a. in Venedig, Berlin, Frankfurt a.M., Los Angeles, New York, Breslau. Möglicherweise werden einige Ausschnitte daraus Einzug in die neue Arbeit erhalten, um die Glaubwürdigkeit der Bilder durch kontrastierende Zusammenstellungen in Frage zu stellen: „What is an original anyway?“.

Die Skizze „Vactor in Venice“ steht jederzeit zur Ansicht zur Verfügung.

What is an original anyway? (Arbeitstitel, 2002)

Auch in Las Vegas ist der Besucher sofort bei Ankunft Teil einer Inszenierung, der er sich nicht entziehen kann. Hat er sich in den 60er Jahren dem nach Mekka größtem Pilgerort der Welt noch mit dem Auto genähert, so landet er heute im Flugzeug, im Minutentakt. Der „Strip“ hat sich entsprechend gewandelt. Die zweidimensionalen Schilder, die Neon-Leuchtreklamen und die bunten Fassaden, ehemals aufgebaut für die mit 35mph vorbeifahrenden Autos, sind durch Pixel und landschaftlich gestaltete Gelände ersetzt worden: vom Zeichen zur Szene.

In den 90ern hat sich Las Vegas erfolgreich zum Freizeitparadies für die ganze Familie gewandelt. Martin Scorsese nannte diese Entwicklung eine „Disneyfication von Sin City“. Mithilfe von „Storyboards“, die gewöhnlich beim Film zum Einsatz kommen, werden die Erlebniswelten zuerst dramaturgisch und dann architektonisch durchgeplant, letztlich mit dem Ziel, den Konsum der Besucher zu steigern. Die neu entstandenen Themenparks benutzen dabei gerne europäische Touristenziele als Referenzorte. Zitiert werden Orte, deren Postkarten-Bilder bereits im kollektiven Gedächtnis verhaftet sind. Die Originalorte produzieren durch diesen Vertrieb ihrer reproduzierbaren „Essenz“ einen Abdruck für Las Vegas.

Das aktuellste Beispiel ist das Casinohotel „Venetian“. In Originalgröße, unter Beratung von Kunstgeschichtlern und Verwendung echten italienischen Marmors, sind die Rialto-Brücke und ihre Umgebung neu geschaffen worden. Die perfekte Kopie erhebt dabei nicht den Anspruch von Authentizität, sie versteht sich als „real fake“. Las Vegas und seine Besucher sind sich des Illusionstheaters bewusst.

Und doch, bei der Eröffnung des „Venetian“ 1999 sah der damalige Bürgermeister von Venedig seine Stadt der Schönheit um ihre Bilder und ihre Geschichte betrogen. Inzwischen versucht Venedig, für seine „Essenz“ ein Copyright in Anspruch zu nehmen und sich durch die Entwicklung einer eigenen „Trademark“ abzusichern.

Durch Hollywood ist Venedig bereits standardisiert und multipliziert worden. Las Vegas geht einen Schritt weiter und macht eine „echte“ Reproduktion begehbar und erlebbar. Der Labyrinth-Effekt, der in Las Vegas kommerziell genutzt wird (wer einmal ins „New York, New York“ hineingerät, findet schwerlich wieder hinaus), hat in Venedig sein kongeniales Vorbild.

Wo liegen die Unterschiede zwischen Original und Abbild? Gegenüber dem Venedig-Touristen nimmt der Besucher des „Venetian“ wohl weniger die historische Substanz wahr, als vielmehr die Masse der anderen Touristen und die Angebote der Dienstleister. Zwar schlüpft er in die ihm angebotenen Rollen, doch bleibt er immer ein Tourist und wird als solcher behandelt. Dass aber auch der Venedig-Tourist als standardisierter Teilnehmer einer wenig romantischen Verkaufsveranstaltung inszeniert wird, diesen Aspekt zeigt „Vactor in Venice“. Hier wie dort sind die Touristen Teil der Inszenierung, sobald sie die Kulisse betreten.

„What is an original anyway?“ Die Frage ist so neu nicht, weder in der Geschichte Venedigs selbst, das sich seinerseits als Komposition von Abbildern entwickelt hat, noch in Las Vegas. Schon der Mafia-Gangster Bugsy Siegel hat 1946 im Flamingo einen Nachtclub aus Hollywood originalgetreu nachgebaut. Wird auch Andrzej Wirth sich in Las Vegas als Gangster ausleben? Oder wird er von alten Sünden erzählen? Wird er vielleicht alles Geld verspielen und obdachlos werden? Es geht darum, den Ort und die Beobachtung mit der Persona Andrzej Wirth sinnvoll zu verflechten.

Wir fragen nach Ähnlichkeiten und Differenzen der Inszenierungen Venedigs und Las Vegas´, deren Besucher und Beobachter wir sind. Nach Möglichkeit werden wir die Betreiber des „Venetian“ befragen.

Das „Venetian“ ist als eine Welt für sich gebaut, mit Innerem und Äußerem in ihrem Inneren. Ein Heraustreten aus dieser Welt und ein Durchstreifen ungewisser Terrains werden wir riskieren müssen. Zum Beispiel auf dem Weg ins „New York, New York“, wo der Müll für alle Besucher sichtbar auf Karren entsorgt wird. Die normalerweise versteckte Dienstleistung wird als Teil der Inszenierung ausgestellt. Wie in Venedig, insbesondere dem nächtlichen Venedig. Das gleichwohl dunkler ausfällt, im Gegensatz zur elektrisierten Wüstenstadt. Und feuchter.

Riassunto, 2002

(Italiano)

Andrzej Wirth e Thomas Martius sono stati insieme a Venezia, intesa come "luogo originale". Si incontrano ora al "Venetian", la riproduzione di Venezia a Las Vegas. Entrambe le città sono teatri labirintici in cui il visitatore è trasformato in attore sul palcoscenico. In che cosa si differenziano le messe in scena? Cosa ha da dirci Andrzej Wirth a questo proposito? E come saranno le immagini di Thomas Martius? Il risultato potrebbe essere un divertente video-essay, al contempo finzione e documentazione.

Vactor in Venice (video, 45 minuti)

Venezia viene mostrata come “walk-in-installation”. Le quinte della citta` trasformano il visitatore in “vactor”, “attore virtuale”. Chiunque e` “always on display”. E, come una figura sul palcoscenico, entra nelle più svariate cornici per poi uscirne. I visitatori si lasciano immortalare davanti a famosi edifici, a loro noti dalle cartoline. Si scambiano a vicenda le macchine fotografiche.

Al centro si colloca Andrzej Wirth, che presenta la sua concezione di “vactors” diventando egli stesso tale. Il professore di scienza del teatro osserva e rimanda le proprie osservazioni sulla sua vita. Da Varsavia, attraverso Brecht, a Kennedy.

Il video è stato sottoposto a un pubblico di specialisti a Venezia, Berlino, Francoforte, Los Angeles, New York, Breslavia. E' possibile che estratti del video siano riutilizzati anche nel nuovo lavoro allo scopo di metter in dubbio la veridicità delle immagini attraverso giustapposizioni contrastanti: “What is an original anyway?”.

La traccia di “Vactor in Venice” è a disposizione per la visione.

What is an original anyway? (titolo provvisorio, 2002)

Anche a Las Vegas il visitatore appena arrivato entra già a far parte di una messa in scena a cui non può sottrarsi. Se negli anni '60 ci si recava in macchina al luogo di pellegrinaggio secondo al mondo soltanto alla Mecca, oggi ci si atterra in una manciata di minuti. Lo strip si è adattato ai tempi. Ai cartelloni bidimensionali, alle pubblicità al neon e alle facciate colorate, allora costruite per le auto che le superavano ai 35mph orari, sono ora sopraggiunti i pixel e le aree pedonali visitabili: dal segno alla scena.

Negli anni '90 Las Vegas è diventata il paradiso del tempo libero di tutta la famiglia. Martin Scorsese ha definito questa trasformazione una “disneyfication of Sin City”. Con il supporto di “storyboards” usate abitualmente nei films, prima si pianifica la drammaturgia, poi l'architettura dei mondi dell'esperienza, allo scopo di raggiungere la meta finale cioè incrementare il consumo dei visitatori. I nuovi parchi tematici sfruttano pertanto volentieri le ambite mete turistiche europee come luoghi referenziali. Si citano luoghi le cui cartoline sono già impresse nella memoria collettiva. Attraverso la distribuzione della loro “essenza” riproducibile i luoghi originali costituiscono una riproduzione per Las Vegas.

L'esempio più attuale è dato dall'hotel casinò “Venetian”. Con la consulenza di storici dell'arte e grazie all'uso di marmi originali veneziani, sono stato riprodotti nelle dimensioni originali il ponte di Rialto e i suoi dintorni. La copia perfetta non rivendica autenticità ma si propone come “real fake”. Las Vegas e i suoi visitatori sono consapevoli dell'illusione teatrale.

Eppure nel 1999, in occasione dell'inaugurazione del “Venetian”, l'allora sindaco di Venezia vide la sua città della bellezza tradita nelle proprie immagini e volti. Nel frattempo Venezia cerca di avanzare l'ipotesi di un copyright della sua “essenza” per assicurasi così il proprio “marchio depositato”.

Hollywood ha già standardizzato e moltiplicato Venezia. Las Vegas fa un passo più in là e realizza una riproduzione vera desiderabile ed esperibile. L'effetto labirinto, sfruttato commercialmente a Las Vegas (una volta entrati nel “New York, New York” non si riesce più ad uscirne), trova in Venezia il suo modello congeniale.

Dov'è la differenza tra originale e modello? Rispetto al turista a Venezia, il visitatore del “Venetian” percepisce meno la sostanza storica che non la massa degli altri turisti e le offerte dei servizi. Si immerge cioè nel ruolo creato per lui pur restando in fondo un turista e come tale considerato. Ma “Vactor in Venice” fa luce sul fatto che anche a Venezia il turista viene messo in scena come partecipante standardizzato di una promozione di vendita molto meno romantica. Sia nell'una che nell'altra città, i turisti diventano parte della messa in scena nell'attimo in cui entrano sulla scena.

“What is an original anyway?” La domanda non è nuova, se si considera la storia sia di Venezia, che da parte sua si è sviluppata come composizione di riproduzioni, sia di Las Vegas. Già nel 1946 Bugsy Siegel, gangster mafioso, aveva fedelmente ricostruito un nightclub di Hollywood a Flamingo. Forse anche Andrzej Wirth diventerà un gangster a Las Vegas? O racconterà dei suoi vecchi peccati? O piuttosto si giocherà tutto il denaro di cui dispone per poi finire tra le file dei senzatetto? Nel progetto si tratta di collegare nel modo migliore il luogo e le considerazioni alla persona di Andrzej Wirth.

Ciò che facciamo è interrogarci su similitudini e differenze nella messa in scena di Venezia e di Las Vegas, di cui siamo visitatori e osservatori. A seconda delle possibilità che ci si offriranno cercheremo di intervistare il gestore del “Venetian”.

Il “Venetian” come mondo costruito a sé, con al suo interno interni ed esterni. Dobbiamo correre il rischio di uscire da questo mondo a sé ed inoltraci in un terreno ignoto. Come quello che incontriamo lungo la strada verso il “New York, New York”, dove le carriole portano via il pattume davanti agli occhi dei visitatori. Il servizio pubblico, che normalmente resta nascosto, entra ora a far parte della messa in scena. Come a Venezia, soprattutto la Venezia notturna. Che risulta pertanto più scura, in contrasto con la città elettrizzata nel deserto. E più umida.